Trump’s Greenland gambit: Could Iceland be next?

So far, it appears she is correct.

The issue now seems to be moving toward the final possibility.

In her book "So You Want to Own Greenland – Lessons from the Vikings to Trump," Arctic affairs researcher Elizabeth Buchanan outlines four potential outcomes for the dispute between U.S. President Donald Trump and Denmark over the world’s largest island.

Among these possibilities, Buchanan suggested that the dispute would conclude with a settlement acceptable to all parties. At the recent Davos forum, Trump reassured allies that he would not annex Greenland by force, citing a "framework" agreement with NATO as the path to resolving the issue.

Did the settlement occur because Europe acted in a semi-unified manner, signaling its willingness to use the "anti-coercion instrument," or because Trump employs escalation as a negotiating tactic without genuinely seeking his maximum demands? The answer may well involve both factors. Certainly, Trump’s reassurance is not final, as evidenced by his warning that Americans "will not forget" Denmark’s refusal to sell the island, should that become the country’s ultimate decision. The concern is that any renewed threats from Trump regarding Greenland may not remain limited to this issue for long.

Why Iceland?

Trump offered several arguments in favor of purchasing Greenland, citing its strategic importance to U.S. national security and the need to prevent China and Russia from establishing military bases there. Even setting aside the fact that the United States could advance its interests through NATO or the 1951 defense agreement with Denmark, Washington could use similar reasoning to expand its influence in both Greenland and Iceland.

Greenland lies closer to the American continent, with its capital, Nuuk, roughly 3,270 kilometers from Washington—slightly closer than the 3,540 kilometers to Copenhagen. Similarly, Iceland is nearer to Greenland, at about 290 kilometers, than to any European land, in this case, the self-governing Danish Faroe Islands, which lie around 410 kilometers away. Geologically, Greenland sits on the North American tectonic plate, while Iceland straddles both the North American and Eurasian plates. Geographically and strategically, Iceland—independent from Denmark since June 1944—may also fall within the sphere of Trump’s ambitions or provocations.

About Geopolitics

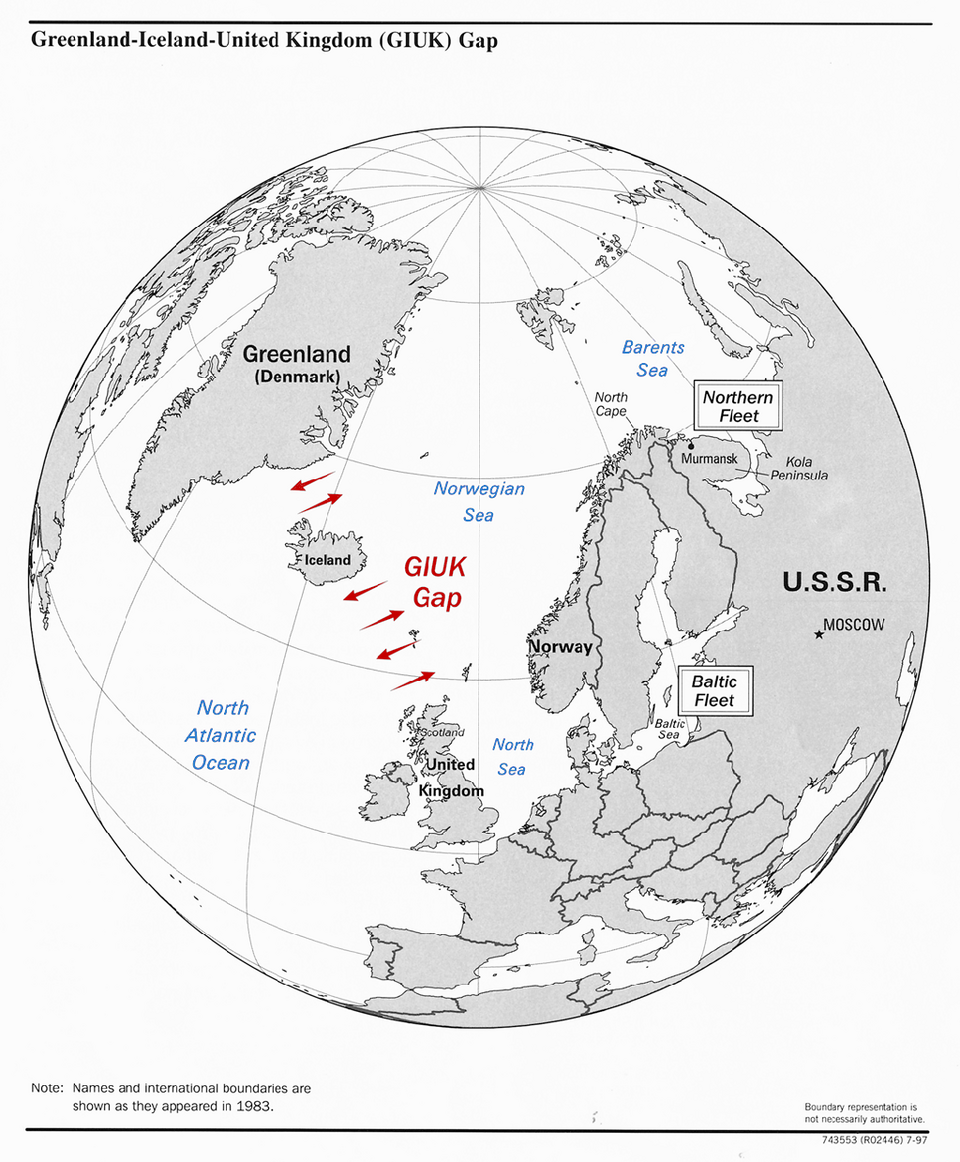

Iceland is located almost at the center of the "GIUK" gap, an acronym formed from the first letters of the regions and countries bordering the area: Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom. This area is crucial for monitoring Russian (and previously Soviet) submarines coming from northern Russia, such as the ports of the Kola Peninsula and Severomorsk, the main naval base of the Northern Fleet. Trump could push for additional military bases in Iceland to enforce stricter control over this gap, in addition to monitoring from the deep seas. U.S. General Christopher Cavoli has said that it is difficult to track submarines once they pass through this bottleneck. The area also serves as a route for transatlantic data and supply transport.

Such a demand, regardless of its upcoming form or the potential accompanying pressures, is merely a mental hypothesis. It should be noted that under a second Trump presidency, mental hypotheses would become a required exercise for European leaders.

Recently, Icelandic political science professor Eirikur Bergmann from the University of Bifröst stated that the Greenland issue forces local leaders to reassess their foreign relations, moving closer to the European Union, particularly for security reasons. He added in an interview with the European platform Euractiv: “All the arguments that the United States presents as reasons for its inevitable acquisition of Greenland would also apply to Iceland.”

Perhaps for this reason, Europeans quickly rallied behind Denmark. They realized that U.S. control of Greenland by force could trigger a dangerously coercive domino effect.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Annahar.

مسنجر

مسنجر

واتساب

واتساب

ثريدز

ثريدز

بريد إلكتروني

بريد إلكتروني

الطباعة

الطباعة

تويتر

تويتر

فيسبوك

فيسبوك