A new mediation axis: Can Saudi Arabia, the US and Egypt break Libya’s deadlock?

On the Libyan street, there are many questions about what appear to be coordinated international moves to try to make a breakthrough in the Libyan crisis. Some view them as an opportunity that can be used to shape a political path with international and regional support aimed at ending the division, while others fear they will be used by those controlling the scene to cement their interests and remain in power.

The German city of Stuttgart hosted a security meeting sponsored by the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), bringing together Saddam Haftar, the deputy commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA in eastern Libya), and Abdul Salam al-Zoubi, the deputy defense minister of Libya’s western-based central government. It was the first such meeting since the death of Libya's Chief of Staff Mohammed Ali Ahmed Al-Haddad late last month in the crash of his aircraft in Turkey.

The meeting between al-Zoubi and Haftar’s son came on the eve of the latter’s trip to Paris, at the official invitation of the Élysée Palace, in a clear sign of Washington’s insistence on coordination and cooperation between eastern and western Libyan forces in preparation for unifying the Libyan military institution, and to avoid any negative fallout from al-Haddad’s departure on this file.

According to information obtained by Annahar, the Stuttgart meeting focused on completing the arrangements for the "Flintlock 26" exercises, which will, for the first time, bring together joint forces from the east and west under the command of AFRICOM, scheduled for this spring in the coastal city of Sirte (central Libya). The focus was mainly on technical details relating to selecting the units participating in the exercise, the distribution of weapons, how to manage operations rooms, as well as securing the exercise zone and its airspace, which is set to begin next month with the transport of weapons to Sirte. However, the absence of Salah al-Namroush, who assumed the post of acting Chief of Staff and is close to Turkey, suggests that Washington is not yet satisfied with his appointment.

This coincides with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia entering the Libyan crisis and mediating between local parties, with the opening of three-way communication lines linking Riyadh, Washington and Cairo to reorganize Libya’s confused political scene.

According to what Annahar has learned, the discussions are centered on avoiding the collapse of the fragile stability, while opening sensitive files, foremost among them the possibility of a quiet transfer of command of the Libyan National Army, amid fears of splits that could affect the stability and cohesion of the institution if General Khalifa Haftar, Saddam’s father, departs.

This comes alongside continued Western doubts about the ability of eastern Libya to loosen its deep ties with its Russian ally, and, on the other side, the fragility affecting the governing structure in western Libya, especially regarding whether the central Government of National Unity can be restored, in light of ambiguity surrounding the health of its prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah. There is also the matter of planned changes within the leadership of the legitimate security agencies, particularly the sensitive position of Chief of Staff after Al-Haddad’s departure, for which three figures are currently considered: Major General Osama al-Juwaili, Lieutenant General Ahmed Ali Abu Shahma, and the Tripoli Military Zone Commander Abdel Baset Marwan.

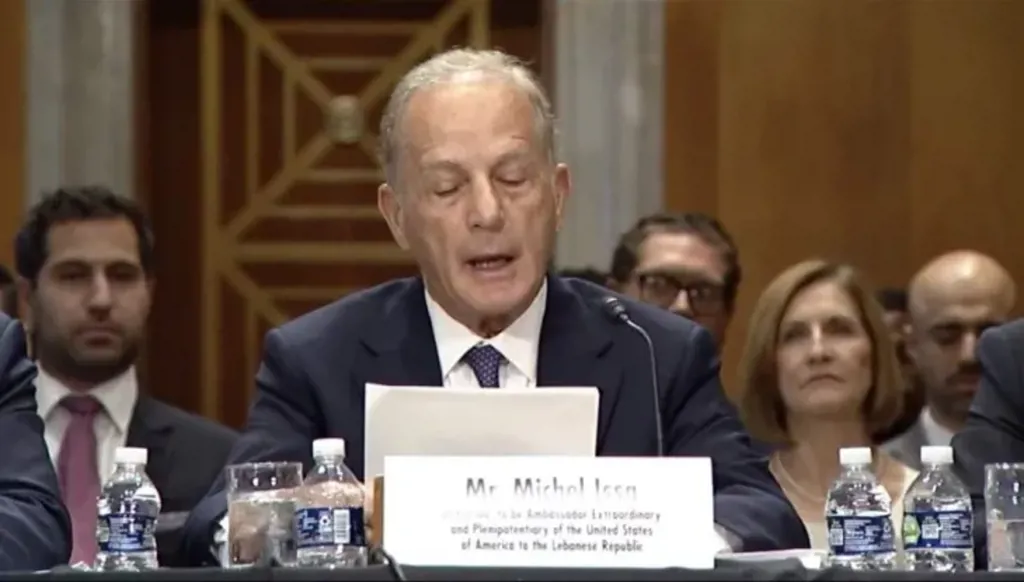

The Libyan file was present on the agenda of the talks held in Cairo last Wednesday by U.S. presidential adviser Mossad Boulos with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Foreign Minister Badr Abdelatty. This coincided with economic talks held in Riyadh with representatives of the western-based central government, as well as meetings conducted by Saudi chargé d’affaires to Libya, Ambassador Abdullah Al-Salmi, with Libyan social groups and political activists.

The Libyan researcher in international politics Osama al-Shahoumi links Saudi Arabia’s entry into the Libyan crisis to what he sees as “a regional and international realization that managing the Libyan crisis at a minimum level is not sufficient, given that the political stalemate and institutional division pose a risk to stability in North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean.”

Al-Shahoumi notes in a statement to Annahar that Riyadh’s move is accompanied by “military meetings led by Washington between forces from the east and west, with the aim of building a gradual state of trust between the two sides, not imposing a forced unification of the military institution. The U.S. approach is based on the principle that any political settlement will remain fragile unless accompanied by realistic security arrangements, even if they are slow.”

Al-Shahoumi, who describes the coordinated efforts between Washington, Riyadh and Cairo as “a potential opportunity, not a ready-made solution,” believes that the Kingdom has advantages that other active regional states do not possess because it has never been a direct party to the Libyan military conflict at any time, which gives it a wider margin of movement as a mediator.

He adds that it also has political, economic and even religious weight that allows it to bring together opposing parties. He adds that Riyadh’s coordination with Washington and Cairo “reduces the chances of international and regional competition, especially from Turkey, which always tries to invest in division to consolidate its influence.”

But at the same time, he conditions the success of these moves on overcoming several challenges, foremost among them the existence of a genuine Libyan will to move beyond the difficult phase the country is going through.

مسنجر

مسنجر

واتساب

واتساب

ثريدز

ثريدز

بريد إلكتروني

بريد إلكتروني

الطباعة

الطباعة

تويتر

تويتر

فيسبوك

فيسبوك