A state at war with itself: Israel’s battle on the internal front

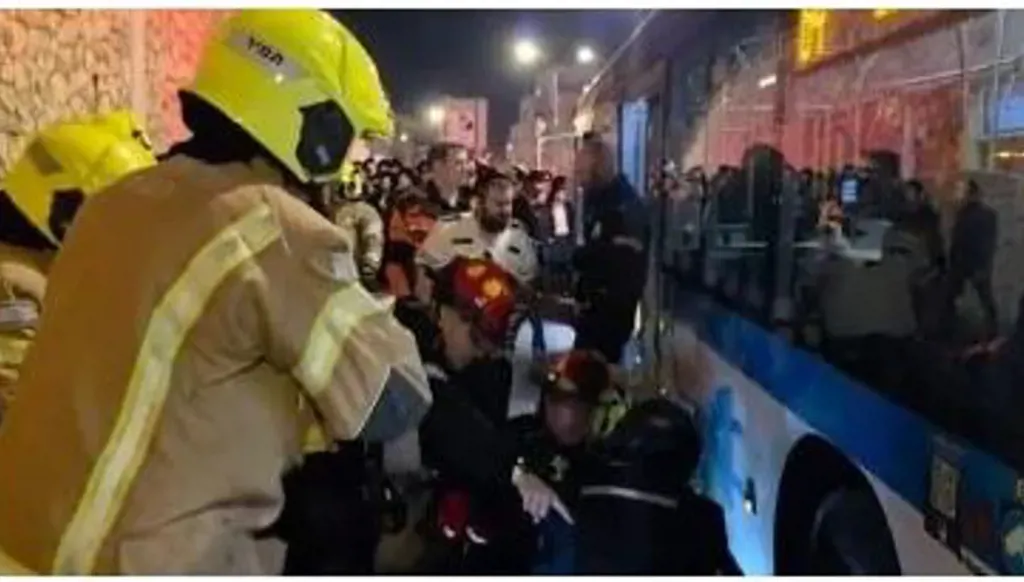

In Jerusalem, incidents do not happen by chance, and questions do not die quickly. When a bus plows into a crowd of Haredi protesters (ultra-Orthodox Jews who oppose military conscription), killing a teenager and injuring others, the scene is not just a tragic traffic accident but a revealing sign of a deeper fracture within a state that refuses to confront its crises and keeps postponing its explosions.

Tens of thousands of Haredim, who make up roughly 13 percent of Israeli society, took to several streets to protest a government decision that reopens the file of mandatory military conscription, a file that was never actually closed but rather hidden under the political table whenever a decision was too difficult to impose.

Police described what happened as a violent disruption of public order: riots, road blockages, burning dumpsters, stone and egg throwing, and attacks on buses and journalists. The Haredi street offered a different account: deliberate ramming, state violence, and a shameless attempt to redefine the killed teenager as a culprit and the victim as a rioter.

But the conflict here is not over how to describe the incident, but over what it means. The core of the issue goes deeper than a bus that lost control or a driver who deliberately rammed forward. It is a draft law that reproduces an old-yet-renewed conflict over exempting the Haredim from military service in exchange for the preservation of the “world of Torah studies”. For the Haredim, conscription is not viewed as a national duty but as a direct intrusion into a closed religious identity built on isolation and on the idea that the survival of “Torah scholars” is a spiritual guarantee for the survival of the people, no less important than tanks and weapons.

On the other side, large segments of Israeli society see the continued collective exemption not as a historical exception anymore, but as a structural injustice that deepens a sharp divide between those who “pay the price” with blood, time, and life, and those who stay outside the wars yet remain within the state and its benefits.

From here, the issue is no longer about conscription, but about justice, and about a social contract that was never clearly defined.

What erupted in Jerusalem is not a passing event but a manifestation of three intertwined crises within the structural foundations of Israel:

First, an identity crisis within Jewish society itself. Which form of Judaism prevails? The closed Torah-oriented Judaism, or the nationalist military state Judaism, or a liberal civil Judaism centered in Tel Aviv? One state tries to be all of these at once and ends up satisfying none.

Second, a crisis of legitimacy for the state and its institutions. When the police become a side in the conflict, and their actions are read as instruments of repression rather than organization, and when the judiciary is viewed as politicized or ineffective, the state loses its power of persuasion and resorts to force as its last language.

Third, a crisis of survival for the current coalition government. It is a far-right government that depends for its survival on Haredi parties, yet at the same time is besieged by the anger of a secular public and an exhausted military reserve asking: Why are we always on the front while they are always outside it?

Here the major paradox is exposed: the government is hostage to its allies and at odds with its society. It has no decisive decision and does not dare to break either side of the equation, so it manages the crisis instead of solving it and postpones the explosion instead of dismantling it.

At this point, it is necessary to try to unpack who supports and who opposes the decision. The ruling coalition is divided within itself. The Haredi parties, Shas and United Torah Judaism, view any infringement on the draft exemption as a direct threat to their political and religious existence and threaten to topple the government if the law is imposed. On the other hand, voices within Likud and other wings of the coalition argue that continuing the exemption can no longer be justified, neither ethically nor militarily, in a time of war and exhaustion. As for Netanyahu, he stands in the middle, not as an arbiter but as a hostage to a harsh equation: if he satisfies the Haredim, he loses the street, and if he satisfies the street, he loses his government.

In a broader context, Israel today appears to be a state fighting on multiple fronts. It is not only Gaza, nor Hezbollah, nor the Houthis, nor Iran that are draining Israel, but this internal fracture that consumes its ability to hold together. Tel Aviv does not actually need conscription as much as it needs to mend its psychological and social fronts. Armies are built on meaning and strategy, not on numbers.

The harsher paradox is that Israel, in this historical moment, is not seeking peace externally, and does not possess a convincing peace internally. It has no settlement project to ease the burden of war, nor a social contract to ease the burden of the state. It is stuck in a gray zone: a war that is not enough to unify its society, and a peace it does not want and does not know how to formulate.

What happened in the streets of Jerusalem was not a bus colliding with a crowd, but a collision between the state and its own definition of itself. The question of who pays the cost of the state’s survival is no longer postponed but posed at the heart of the city that has long been a mirror for all crises. In Jerusalem, as in Israel as a whole, the state continues to walk over its own cracks, pretending to be cohesive while the gap widens beneath its feet. A complicated scene in which no peace brings relief, no war is sufficient, and a government struggles to keep the system running until further notice.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Annahar

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook