The bold cinema of Youssef Chahine: Passion, politics, and legacy

“Cinema takes my breath away; and I’ve been living in this state for more than sixty years.” That’s what Youssef Chahine (1926–2008) told me, laughing with the innocence of a child, during our last meeting in Beirut at the launch of "Alexandria... New York," his penultimate film. A recollection of a complex relationship with America, the film gradually becomes an anthem to cinema itself, as Chahine, in a fashion befitting his genius no longer saw any difference between his life inside and outside the cinema.

That day, a simple yet complex question struck me: how can a director present subjectivity without losing the necessary distance from his subject? Chahine answered that an experience becomes immortal only after being lived countless times—lived in writing, lived in filming—until it finally settles on the screen. His films were charged with nostalgia and emotion.

Chahine reached a level of importance, recognition, and fame of no Arab director before him, receiving the 50th Anniversary Lifetime Achievement Award during the the Cannes Film Festival in 1997. He began with the concerns and issues of Egyptian society, addressing his world through a cinematic language always driven by his roots. In Chahine's words, “this is me, this is my history, and these are my people.” His works, which consistently generated wide debates, bans, exclusions, and misunderstandings, never rested on a single interpretation, remaining open to reinterpretation with changing moods. Some even predicted events to come, as in "Chaos," his cinematic testament that envisioned the January 25th revolution, the date on which he was born 100 years ago.

Chahine employed foreign technicians, becoming a symbol of East–West cooperation without abandoning the pure Egyptian spirit. This makes his cinema a living document, allowing us to glimpse different periods in atypically advanced visuals and audio than most Egyptian productions of the time. His fame transcended geographical boundaries, and he was one of the few Arab filmmakers known to educated, informed, and curious European audiences—especially in France, which embraced and supported his excellence.

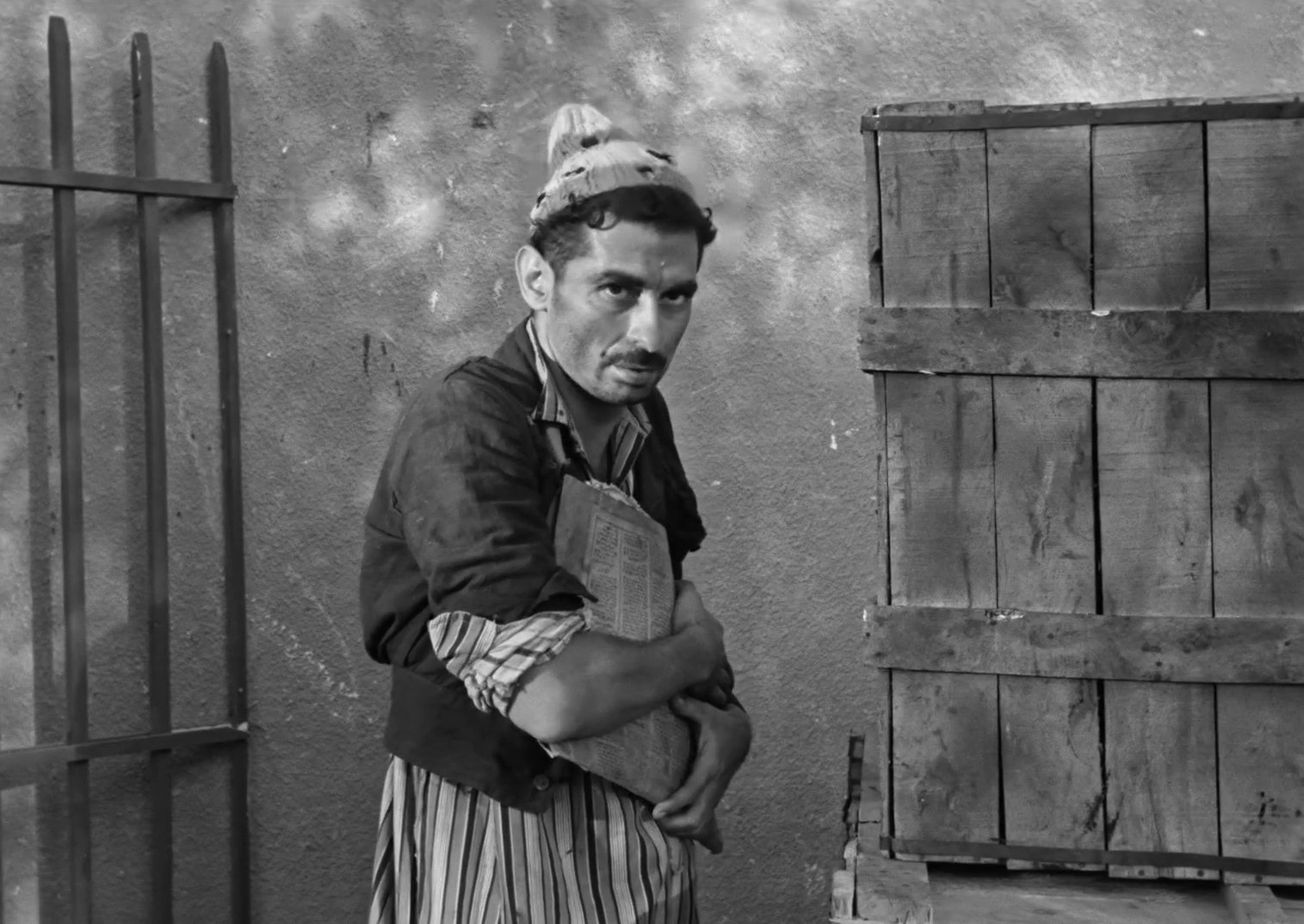

Of Zahle roots, Alexandrian to the core, Francophone and cosmopolitan in taste, enlightened and free—this is part of what Chahine was, a figure who embodied contradictions, identities, and cultures, even sexual tendencies. He studied Shakespeare, acted, and directed on the Victoria College stage in Alexandria before traveling in 1946 to the United States to study acting and directing at Pasadena University. There, he realized that his true place was behind the camera, not in front of it, and so he distanced himself from the traditional dream of stardom, although he would later embody an iconic role: Qinawi in "Cairo Station." Since then, Chahine sought an “alternative self,” representing his point of view through his actors and allowing his unique style to unfold through intensity of expression and rapid movement.

With "Cairo Station" (1958), Chahine reached the peak of artistic avant-garde. This masterpiece, now considered one of the greatest Arab films, unfolds over the course of a single day at a train station, where the fates of crushed characters intersect. Chahine portrayed the role of Qinawi, a physically deformed and psychologically broken man, and, thanks to a tight cinematic construction, succeeded in drawing the audience’s sympathy toward a deeply complex character.

After the July Revolution, Chahine’s films reflected the strained social reality and the desire for change. He engaged directly with politics in "Jamila" (1958), a tribute to the Algerian revolution, then entered his maturity with "Saladin" (1963), which placed Arab cinema on the map of grand production. The defeat of 1967 pushed him to confront himself and his nation, resulting in his masterpiece "The Land," where the farmer’s story became an epic human tale of resistance against oppression. Chahine viewed the setback as the defeat of a civilizational project rather than that of a people, turning the film into a visual statement on the continuation of struggle despite defeat.

“The Land” closed one phase and opened another, more closely linked to political and social transformations. This phase included "The Choice" and "The Sparrow" (the latter about Egyptians’ struggle to regain Sinai), followed by "The Return of the Prodigal Son." It reached its peak with "Alexandria… Why?" (1978), his cinematic ode to his hometown, followed by "An Egyptian Story" and "Alexandria Again and Forever," completing his personal trilogy. The trilogy received many accusations, including of narcissism and narrative slackness, making it a challenging watch for audiences unfamiliar with Chahine’s cinematic world. But, despite this, he was undeniably the first Arab director to delve into memory.

Visually, he loved camera movement and believed that one does not need to be a director to shoot a film with static shots, as even a soldier might succeed at that task. In my discussions with him, he said: “I don’t like customs that classify you into a certain 'dogma;' I find all labels 'lame' and meaningless. No decisions should be made in advance regarding filming—the scene itself dictates how you film it… I can sit with you and discuss the shape–content equation for two years. In short, I say: the form must serve the content.”

Since the mid-nineties, a phase inaugurated by "The Emigrant," Chahine’s films—despite varying in quality—continued to provoke censorship and challenge extremist factions in his country. “Every good book containing bold ideas is destined to be banned, forcing the majority into self-censorship,” he once said—a principle he never followed, remaining the candid voice who did not hesitate to call George W. Bush a 'donkey' during a press conference after September 11th. In the late nineties, he gave us "Destiny," a project overtly nationalist in nature, intending to affirm the role of Arabs in establishing human civilization. While the West was drowning in ignorance and darkness, the Arabs were enjoying knowledge, light, civilization, and progress. Yet this did not prevent him from considering all Arab leaders tyrants. He was unmatched in his acuity, even if his political positions were not always taken seriously.

His last films were variations on themes that accompanied him for over half a century: freedom, identity, conflict, and cinema as a subtle act of defiance. They seemed like a life synopsis.

Youssef Chahine passed away at 82 in the summer of 2008, but his cinematic struggle did not end. His films remain alive, discussed, and re-read, bearing witness to the journey of an artist whom the world could not subdue; rather, he drew it toward him. He was not concerned with how he expressed what he wanted to express, nor at what cost, but with the importance of the message itself. Often, he stood alone in his frankness, saying what others did not dare to in an Arab world accustomed to either tumult or silence. In a profession where many prefer to hide in vagaries, Chahine chose clarity and rigor.

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook