Can the arrest of Maduro dismantle the shadow economy extending from Venezuela to Iran?

The most daring American operations to change a political regime since the Iraq invasion in 2003 culminate in a year-long campaign launched by U.S. President Donald Trump against Caracas, under the pretext of combatting the flooding of the United States with cocaine and fentanyl. This campaign placed Trump in an open confrontation with Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, as a leader of an intertwined network of smuggling and organized crime.

The crucial question arising today is whether the arrest of Maduro and his wife, their air transfer to the United States, and the commencement of legal proceedings against them are sufficient to cut off the smuggling arteries that have intertwined across the Latin continent, reaching Europe and the Middle East?

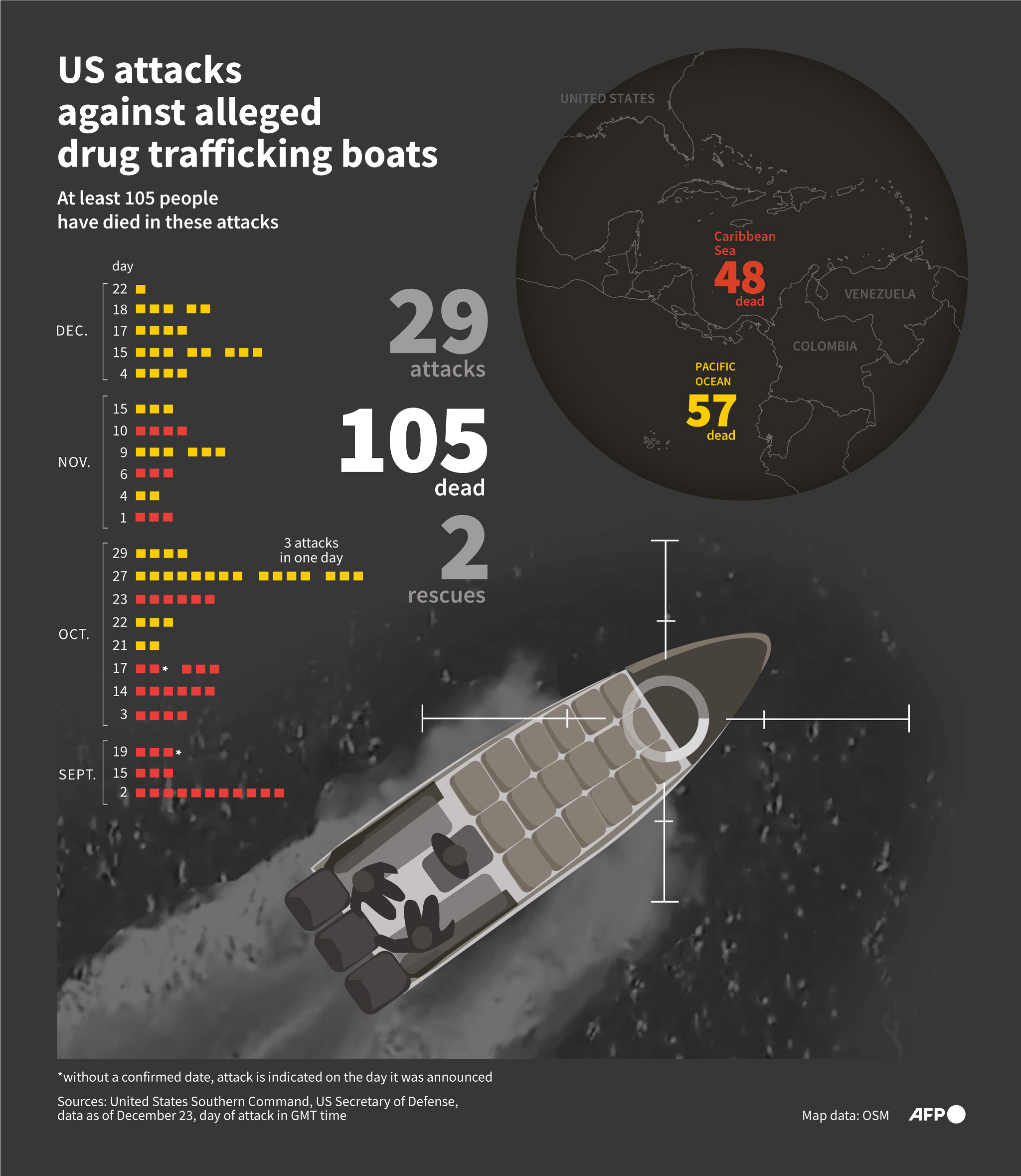

Washington considered Caracas a key link in the regional drug corridor, as according to the American narrative, it facilitates the movement of cocaine from Colombia through Venezuelan territory before shipping it by sea and air to the United States, the Caribbean, and Europe. In this context, Trump eliminated oil privileges granted to Caracas during his predecessor Joe Biden's term, including a license to export a portion of Venezuelan oil to the American market despite sanctions. He did not stop there; he later imposed a 25% tariff on countries buying Venezuelan oil in an attempt to financially strangle the regime.

On August 8, 2025, the American administration escalated to an unprecedented level, announcing a $50 million reward for information leading to Maduro's arrest, designating him a "global terrorist leader" of the cartel "Cartel de los Soles," an accusation Maduro vehemently denies. Less than two weeks later, on August 19, Washington translated its threats into action by deploying three missile destroyers off the Venezuelan coast, subsequently boosting its presence with three amphibious assault ships carrying approximately six thousand troops, along with advanced aircraft including F-35 fighters.

However, the image of the "Cartel de los Soles" seems less cohesive than claimed. According to Phil Johnson, an analyst based in Caracas with the "International Crisis Group," it is a loose network mostly consisting of officers facilitating drug trafficking in exchange for bribes, rather than a centrally organized entity.

There is variance in the details concerning Venezuela's precise role within the complex drug trafficking network. The American prosecution must prove that fentanyl specifically comes from Venezuelan territory, while facts indicate that the largest amounts of this deadly substance enter the U.S. via Mexico, often manufactured from precursor chemicals sourced from Asia. Meanwhile, most cocaine is produced in Colombia and the Andes, with Venezuela and the Caribbean used as transit paths and launching points toward European markets.

Iran and "Hezbollah"

Nevertheless, investigative reports and congressional testimonies issued in 2024 and 2025 link the Venezuelan government to illegal transnational networks including countries and groups such as Iran and "Hezbollah." These reports describe Venezuela as a "permissive environment" where government interests intersect with those networks to facilitate drug trafficking, money laundering, and circumventing international sanctions.

In a congressional testimony last October, Matthew Levitt, director of the Janet W. Reinard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at "The Washington Institute", said this cooperation is based on a logic of "mutual survival." He added, "Hezbollah is no longer just a guest in Latin America, but has become a professional money laundering engineer." According to Levitt, the organization exploited Venezuela's free trade zones and gold trade to detach its financing from the traditional banking system, building a parallel economy serving its regional ambitions and Caracas' need to circumvent sanctions.

However, Maduro's removal does not necessarily mean dismantling this complex scene. Mick Mulroy, a former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense and retired paramilitary officer with the CIA, expresses doubt about the impact of the Venezuelan president's removal on drug trafficking. He told "An-Nahar": "It is unclear to what extent this would affect the system, which still exists, but without Maduro."

In a remarkable press conference, Trump did not rule out directing another strike against Venezuela, saying Washington "will govern Venezuela for a while," in a statement that rekindled memories of direct political intervention scenarios.

In this context, Norman Roule, a former CIA official, told "An-Nahar" that the Trump administration will demand any future Venezuelan government to sever all ties with Iranian intelligence agencies and "Hezbollah," as a fundamental condition to lift international isolation.

It is clear that a decision to dismantle transcontinental networks has been made, and Washington realizes this requires more than a bold operation of any scale. Mulroy says: "The ongoing American strikes have weakened the network, and I believe they will continue."

مسنجر

مسنجر

واتساب

واتساب

ثريدز

ثريدز

بريد إلكتروني

بريد إلكتروني

الطباعة

الطباعة

تويتر

تويتر

فيسبوك

فيسبوك