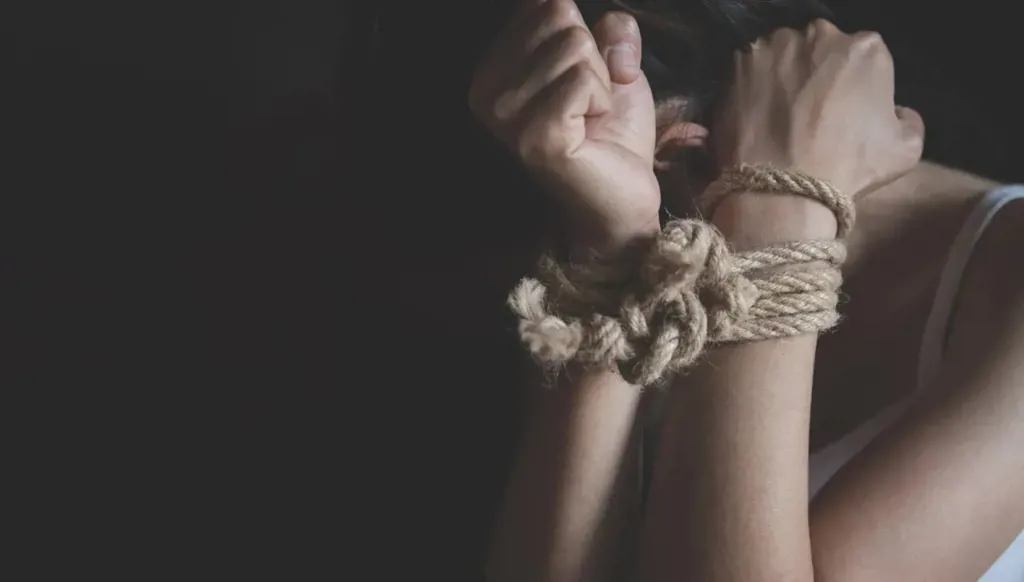

Behind closed doors: Abduction and assault of Syria’s Alawite women

The British Broadcasting Corporation, BBC, conducted an investigation into Syrian women from the Alawite community who were subjected to abduction and assault. The names of the victims and their families who spoke to the BBC were changed at their request to protect their privacy.

“Ramia was preparing a mate infusion to drink with her mother and siblings near her home in the countryside of Latakia. She had arranged everything for a small outing in an agricultural area of her village. It was still morning, the weather was pleasant, and the farmers were tending to their land,” she told the BBC. “Her mother and siblings were about to meet her when a white car stopped. Three armed men got out, claiming to be members of the public security forces. After a brief improvised conversation, they forced her into the car,” she recounted.

Ramia added, “The car drove in the opposite direction of our home and then left the village. That’s when I realized I had been kidnapped.” She continued, “They beat me. I started crying and screaming, but they continued hitting me even harder. One of them asked if I was Sunni or Alawite. When I answered that I was Alawite, they began insulting my sect.”

After several hours, Ramia, who was not yet twenty, found herself in a location in Idlib, according to what she overheard her captors saying. They had forced her to wear a niqab and placed her in an underground room, locking the door. The room contained a bed, pillows, personal items, and a condom. She spoke in a sorrowful voice: “I tried to hide it, but I knew it would not help.”

Ramia is one of dozens of Alawite women reported kidnapped since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024. Various human rights organizations have documented their cases, with numbers differing from one organization to another. The Syrian Women’s Lobby, a women’s rights advocacy group, told the BBC that it had received reports of more than 80 women going missing and verified 26 cases as abductions. The vast majority of those missing belong to the Alawite community, according to the lobby.

The Syrian authorities deny the existence of such incidents, acknowledging only a single case of abduction during a press conference in early November. However, a security source in one of Syria’s coastal regions, who requested anonymity, confirmed to the BBC that kidnappings had occurred. He added that “investigations were opened” and that “disciplinary measures were taken” against those involved, including security personnel.

The BBC managed to reach five of these abducted girls and their families. Some shared the details of their kidnappings and assaults, while the fate of others remains unknown.

“Alawite Women Were Made to Be Captives”

In its investigation, the BBC reported that Ramia was one of the abducted. She was held for two days, during which she attempted to escape once and tried to take her own life twice. Her captor did not speak Arabic fluently. She described his features as appearing Asian and believes he was one of the Uyghur fighters who joined armed Islamist factions in Syria. While in captivity, she said her captor removed her niqab and took photos of her, claiming he would send them “to the Emir, who would decide her fate.” However, the fighter’s wife, who was in the same house with their children, told Ramia that the photo “would be used to set her price if she were sold.”

Ramia also recalled asking the captor’s wife how many women had been kidnapped before her. The wife replied, “Many.” According to Ramia, the wife added that “some are raped and sent back to their families, while others are sold.” The BBC could not independently verify cases of “selling,” but more than one survivor said they had received similar threats.

One returnee, Nesma, a mother in her thirties, came back to her family after being “completely desperate,” she told the BBC.

She believes she was also held in Idlib after being abducted from rural Latakia. However, her captors were Syrian, not foreign fighters, according to her account.

Nesma said she was kept for seven days in a large room with high windows in what appeared to be an industrial facility. Three men would come regularly to interrogate her about the residents of her village and any links to the former regime. She continued, “They insulted me because of my sect, saying that Alawite women were created to be captives.” According to her testimony, Nesma was raped multiple times. She recalled, “All I could think about was dying. I would die, and my child would be left without a mother.”

Lin, another young woman under twenty, was beaten, threatened with weapons, and raped daily, according to her mother. Her captor never uncovered his face and did not speak Arabic fluently. “He was a foreign fighter,” said Hasna, Lin’s mother. She added that he would bring food for her daughter daily, stay for hours, boast about participating in massacres along the Syrian coast, and insult the Alawite sect.

Lin’s mother continued: “He described our daughters as concubines, saying they did not worship God.” However, when Lin spoke to him about religion, her mother said that “his attitude changed,” and he began treating her more gently, according to the investigation.

Patterns of Harm

Alawites are generally perceived as supporters of former President Bashar al-Assad, who belongs to the same sect, even though many of them have faced repression and arrest for their opposition political activities. After the fall of Assad’s rule, fears of retaliatory attacks increased, especially amid the bloody violence and mass killings witnessed along the coast in March.

Christine Bakerly, Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International, told the BBC that survivors’ testimonies indicated “patterns of harm that go beyond the abduction itself. Families received evidence showing that some of the women were subjected to physical abuse. In three cases documented by the organization, there were strong indications that the abductees were forced into marriage, including at least one minor.”

Amnesty International reported that in nearly all cases it documented, families had reported the abductions to the police or security agencies but received no meaningful updates and saw no tangible progress in investigations. Bakerly emphasized: “Those responsible must be held accountable and compensation provided. Failing to do so constitutes a human rights violation.”

Meanwhile, in early November, the Syrian Ministry of Interior announced the results of a committee it had formed during the summer to examine complaints and allegations regarding the abduction of women and girls along the Syrian coast. The ministry reported that 41 out of 42 allegations were found to be untrue, according to the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA).

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, Nour al-Din al-Baba, stated that the disappearances ranged from “voluntary elopement with a romantic partner” to “temporary absence at friends’ or relatives’ homes,” or “escape from domestic violence,” in addition to false claims, criminal acts, and cases involving “prostitution or blackmail.”

The BBC contacted the Syrian Ministry of Interior, but it declined to comment. However, a security source in one of the coastal regions, speaking anonymously, told the BBC that there were “undisciplined actions by some personnel carrying out temporary kidnappings for financial extortion, recklessness, or personal reasons,” such as revenge against relatives of officers or individuals close to the former regime.

He added: “Some cases were uncovered and the personnel involved were immediately dismissed. At the same time, there are many cases claimed as abductions, but in reality, these people left their homes or towns of their own free will,” according to the source.

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook