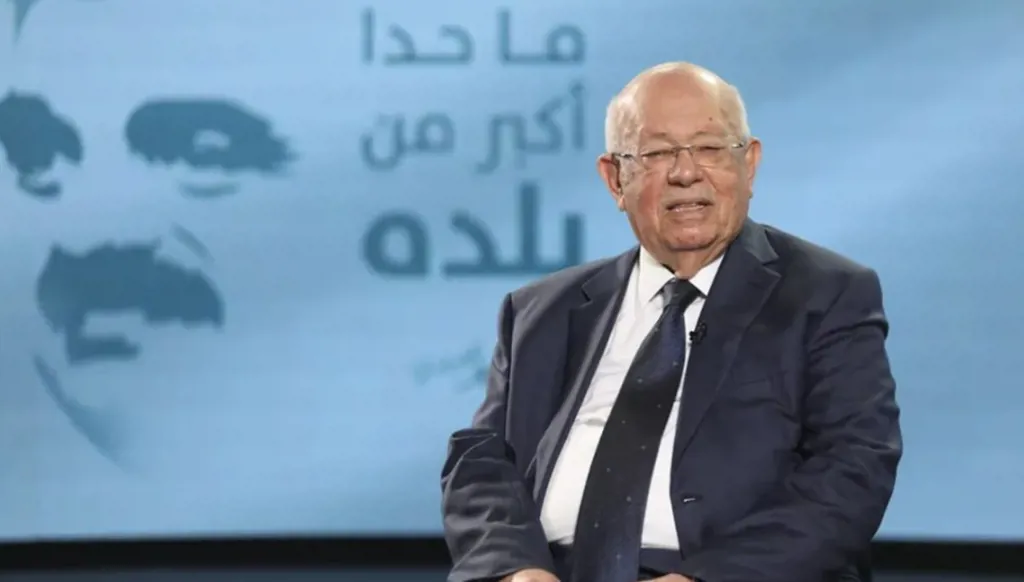

Derbas recalls Hariri’s "revival project" 21 years after assassination

Twenty-one years after the assassination of martyred former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, former minister Rashid Derbas recalled moments that, in his view, capture the man beyond politics and official positions - returning him to the essence Derbas says he knew closely.

Derbas told Annahar that the first thing that comes to mind when Hariri’s name is mentioned is that his assassination was not merely the targeting of an individual, but a deliberate attempt to kill a national revival project for a country exhausted by years of war.

“It was a real revival, with its tools, will and reference,” he said. “That is why I always recall a picture from 1995, after the war had laid down its burdens at one of its stages.”

Derbas recounted how the Rahbat neighborhood in Al-Qubba, Tripoli, had turned into a battlefield and suffered heavy shelling. One day, the Oger company arrived — on Hariri’s instructions and at his expense — to remove the rubble. The challenge was where to dump it, so an agreement was reached with the mayor of Al-Mina, Abdul Qadir Alameddine, to dispose of it along the coast of Mina, Tripoli.

“The rubble turned into a unique promenade, seven kilometers long,” Derbas said, noting it was later improved by UNDP to high standards implemented by Germany and Britain. “Today, it is a destination for strollers from Tripoli, the north, and all of Lebanon.”

For Derbas, the episode was evidence of Hariri’s mindset.

“He turned the rubble into a park, a new life,” he said. “At the same time, the reconstruction of the Rahbat neighborhood was completed: 72 buildings were erected, each five stories high, with two apartments per floor, complete infrastructure, three schools, and renovations of both a mosque and a church, since the neighborhood was mixed.”

“He always thought about development — about turning chaos into prosperity — and cared deeply about preserving demographic diversity,” Derbas added.

Before speaking about his last meeting with Hariri, Derbas recalled a story he said he heard from Fadl Shalaq. After Israel’s withdrawal from Beirut, Hariri volunteered to remove the effects of war from the city. He visited the former confrontation lines at night, when the city was engulfed in complete darkness.

“We will conquer the darkness with light,” Hariri said at the time, according to Derbas, and ordered the purchase of the largest generator available to illuminate the area. Derbas said the moment later became a starting point for rebuilding Beirut as a city of life and future, even as hostilities remained close.

As for the last conversation between them, Derbas said it took place in the first half of December 2004. He visited Hariri at his home with Shalaq to discuss the marriage contract of Shalaq’s son to Hariri’s daughter. Hariri apologized for not attending the contract because he would be outside Lebanon, but promised to attend the dinner.

During their political conversation, Derbas recalled Hariri telling him: “I swear to you by my daughter Hind, I do not want to be prime minister now. But I will run in the elections everywhere. All the deposit I had is gone. Since I do not want to be prime minister, what could they do to me? They have no choice but to kill me.”

Hariri then paused and added: “I do not think they dare.”

On the day of the dinner, Abu Tareq Al-Arab, who was responsible for arrangements, arrived and asked about the president’s table. After taking photos, he told them he had come from the patriarch, and an agreement was made to contest the elections under the 1960 law.

Derbas said what worried Hariri was not fear for himself, but his larger dream.

“He had the ambition for Lebanon to become a jewel,” Derbas said. “He believed it was possible, relying on significant Saudi support, and he was willing to spend his money.”

Derbas said Hariri also relied on a Saudi-Syrian understanding that allowed him to pursue his project, as well as an international atmosphere that emerged after the Madrid Conference. But that atmosphere later changed, and Hariri began to feel the circumstances that had enabled his dreams were clouding.

“He was preoccupied, but stubborn,” Derbas said. “If he did not succeed from one angle, he would circle around and achieve it from another.”

Derbas believes that if Hariri were alive today, he would not have accepted the building collapses happening in Tripoli and would have intervened directly — perhaps by establishing temporary shelters for residents, as he did in previous phases.

“He would have moved,” Derbas said. “He would have prevented things from reaching this extent.”

Reflecting on Hariri’s death, Derbas said: “The loss is not only personal. Everyone grieves for their friend. But here, the loss is public. We lost him, and all who were attached to him lost him too.”

He revealed that Hariri repeatedly tried to attract him into political life and even nominated him in the 1996 elections.

He concluded: “His loss is not just the loss of an individual, but the loss of a national project.”

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook