A reevaluation of the Shah: History on trial

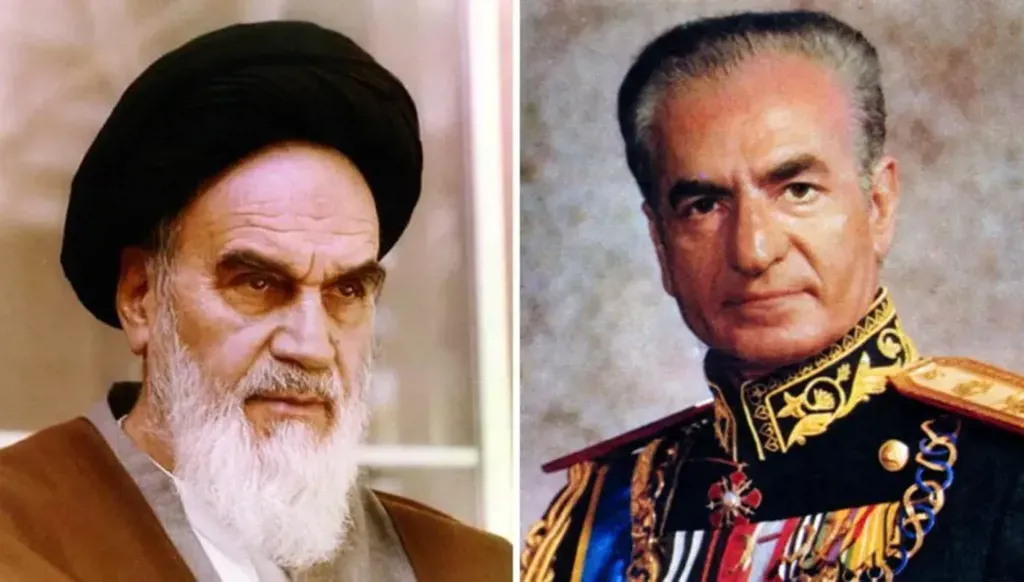

The Islamic Republic of Iran is currently facing the largest wave of popular protests since its founding in 1979. This context may prompt renewed interest in the country’s history under the Shah’s rule. Research by a serious Indian scholar specializing in the region highlights three main points often cited in the “demonization” of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi: that he was a dictator, that he acted as a puppet of the United States following the CIA-backed coup that returned him to power in 1953, and that he oversaw a brutally repressive secret police, the SAVAK. While each of these claims contains elements of truth, they also involve significant exaggeration or misrepresentation.

Was the Shah a dictator? Technically, he was a monarch. By Western standards we might call him a dictator, but under his rule, Iranians enjoyed more political, economic, and social freedoms than under the religious regime that began in 1979 and continues today. In 1978, demonstrations in Tehran called for the “downfall of the bloodsucking Shah.” Can anyone imagine a similar protest under the current regime, shouting “Down with Khomeini, the bloodsucker”? Certainly not—such expressions would likely be met with execution.

During the Shah’s reign, various anti-government groups—including liberal university students, communists from the Tudeh Party, and Islamist extremists—actively opposed him. The terrorist group “Fedayeen of Islam” even attempted to assassinate the Shah, firing five shots; four missed, and the fifth struck his shoulder. Ironically, many of these anti-Shah groups were later brutally suppressed by Khomeini’s regime after the revolution.

Iran had a freely elected parliament, and at one point, Prime Minister Mossadegh became so powerful that the Shah temporarily fled the country in 1953.

If the Shah were truly a dictator, the 1979 revolution against him might never have happened. Yet the lingering Soviet narrative portrayed him as an American puppet. It is important to remember that this was during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union were competing for influence over Iran, a country of immense strategic importance due to its resources, location, and political position. The Soviets supported communist groups within Iran to destabilize the Shah’s government, and anti-Shah propaganda was broadcast for seven hours daily from Soviet radio stations near Iran’s borders.

While the Shah was a “Westernized” leader and the United States naturally wielded influence during his rule, he was far from being a mere puppet. In fact, a CIA psychological study described him as a megalomaniac driven by a sense of grandeur, with his own plans and little concern for U.S. interests—hardly the characteristics of a subordinate leader.

What about the CIA-orchestrated coup in Iran in 1953? It was a coup intended to prevent another coup or the success of a potential one. Contrary to popular belief, the Shah was not “restored to power” by the CIA in 1953. He had ascended the throne in 1941—twelve years before the so-called “coup” and six years before the CIA was even established. The key nuance is that the CIA carried out a coup and assisted the Shah, who had fled the country for three or four days. This is what actually happened at the time.

Prime Minister Mossadegh was a powerful and ambitiously populist leader. He nationalized the oil industry in 1951, but the move proved disastrous: within two years, Iranian oil production fell by about 95 percent, British technicians withdrew, and Iranian technicians lacked the knowledge necessary to operate the refineries. In this context, the Shah attempted to remove Mossadegh from office but failed, despite being considered a “very harsh dictator.” Fearing a coup against him or even assassination, he fled to Italy for two days.

Meanwhile, Western oil interests and the deep state (CIA and MI6) were waiting for an opportunity to remove Mossadegh. That opportunity came in 1953, when the CIA executed its coup—essentially, a coup designed to prevent another coup.

What about the notorious SAVAK, infamous for its brutal actions? After the 1953 coup, the Shah sought Western support, and in 1957, SAVAK was established with the assistance of the American CIA and British MI6. Indeed, SAVAK was ruthless, operating above the law, conducting espionage, making arrests, and using torture.

However, when the Islamic Revolution succeeded, SAVAK was not dismantled—it was simply renamed SAVAMA. General Hossein Fardoust, who had been deputy head of SAVAK, became the head of SAVAMA. Much of the previous infrastructure, files, intelligence network, methods of torture, and even many former SAVAK agents continued to function under Khomeini’s regime.

This aspect is rarely discussed, especially by the Shah’s critics. While it belongs to history, it does not diminish the fact that relations between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the United States deteriorated sharply afterward. Supporters of Khomeini and his revolution stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking approximately 58 diplomats and staff hostage for over two years. The Carter administration attempted a military-intelligence operation to rescue them, but it ended in failure in the Iranian desert of Tabas. This only strengthened Iran’s stance, allowing it to publicize its hostility toward the United States and maintain control over the hostages.

Iran also sought to influence the approaching U.S. presidential election, suggesting that it might release the hostages if Carter failed to win reelection and Ronald Reagan succeeded him. This marked Iran’s first direct intervention in American political life. The events that followed are well known, forming a history defined by both expressed and practiced hostility.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Annahar.

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook