From Global Coordination to Local Collapse: An Emerging-Market Reading

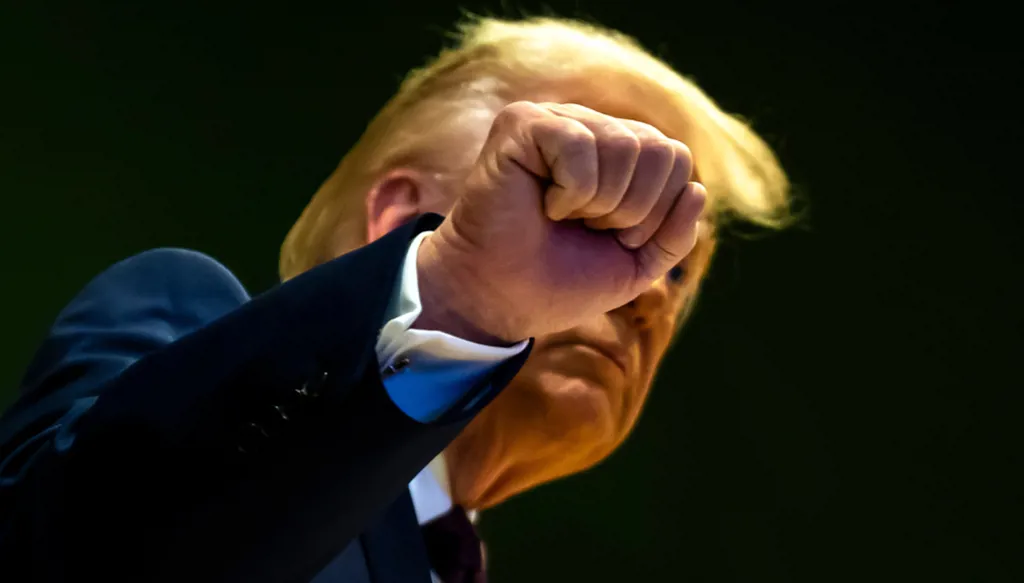

The second term of Donald Trump did not begin with adjustment; it began with disruption. Within weeks, long-standing assumptions about alliances, trade, security guarantees, and multilateral discipline were openly questioned, and sometimes discarded outright. This was not diplomatic noise or negotiation theatrics. It was a deliberate stress test of the post-Cold War order. By treating rules as optional, alliances as transactional, and institutions as expendable, Trump planted the seed of a new world order; one defined less by coordination and more by leverage, less by predictability and more by power asymmetry.

What made this moment consequential was not rhetoric alone, but sequencing. The diplomatic shock came before the global system had fully absorbed the lessons of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), before climate risk was institutionally priced, before debt overhangs in emerging markets were resolved, and before security architectures adapted to multipolar reality. The result was not creative destruction; it was systemic disorientation. Markets recalibrated faster than institutions. Risk was repriced unevenly. And the burden of uncertainty migrated, once again, downward.

For advanced economies, this rupture translated into strategic flexibility. For emerging markets, it translated into fragility. Trade norms weakened just as export-dependent economies sought recovery. Security ambiguity intensified just as geopolitical insurance became more expensive. Monetary fragmentation deepened just as dollar dependence became harder to escape. What appeared, from Washington, as assertive sovereignty was experienced elsewhere as disorder without a referee.

This is the context in which global coordination platforms, from Davos to the G20, from COP to BRICS, must now be read. Not as neutral forums for collective problem-solving, but as stages struggling to remain relevant in a world where power increasingly bypasses process. The question is no longer whether these gatherings matter in principle. It is whether they can still discipline outcomes in a system that has begun to reward unilateralism, delay, and strategic ambiguity.

Lebanon, like many emerging economies, does not observe this shift from a distance. It absorbs it through higher risk premia, faster de-risking, delayed crisis resolution, and shrinking policy space. In that sense, Trump’s second-term shock was not an American event. It was a global inflection point whose costs are still being settled disproportionately, and quietly outside the rooms where global order is discussed.

That rupture matters because it changed not only how power is exercised, but how coordination is simulated. As the international order drifted from rules to leverage, global summits multiplied rather than consolidated. Meetings became substitutes for decision, choreography replaced hierarchy, and dialogue increasingly stood in for enforcement. The more fragmented the system became, the more often leaders convened producing the appearance of governance without its discipline. In this environment, uncertainty is not resolved; it is managed rhetorically and redistributed economically. What looks, from the center, like continuous engagement is experienced on the periphery as prolonged exposure to unresolved risk. It is against this backdrop, not in spite of it, that the global calendar is now crowded with summits, even as the global system itself feels increasingly unmanaged.

The global calendar is crowded with summits, yet the global system feels increasingly unmanaged. From the G20 to COP, from BRICS to Davos, leaders meet with remarkable frequency to discuss monetary stability, financial stability, climate risk, financial inclusion, poverty, food security, mounting international debt, and geopolitical uncertainty. The repetition of these gatherings gives the impression of constant engagement, but for emerging economies the outcome is not stability. It is exposure.

The problem is not that global coordination platforms exist; it is that they have evolved into spaces where alignment is discussed without being enforced, and where delay is normalized as prudence. In advanced economies, delay is a policy choice with buffers. In emerging markets, delay is a destructive force. Time itself becomes the transmission channel through which global indecision turns into local collapse.

Lebanon illustrates this dynamic with painful clarity. Its financial crisis did not deepen because the problem was misunderstood; it deepened because resolution was perpetually deferred. While global institutions debated sequencing, conditionality, and governance, balance sheets deteriorated, confidence evaporated, and informality expanded. What appeared globally as “careful process” was experienced locally as institutional asphyxiation. No summit had a mechanism to arrest the damage once it began.

This is where global governance theater becomes economically consequential. When coordination fails to produce credible, time-bound action, markets do not wait. They price uncertainty immediately, and they do so asymmetrically. Emerging markets face higher risk premia not because their fundamentals deteriorate overnight, but because the global system has no reliable way to contain uncertainty before it metastasizes. Capital withdraws, maturities shorten, and currencies weaken, not as punishment, but as rational self-protection in a fragmented order.

The same logic governs de-risking. Global forums regularly endorse higher compliance standards, stronger safeguards, and tighter controls in the name of financial integrity. Yet the cost of implementation is quietly outsourced to weaker banking systems. For countries like Lebanon, this results in the loss of correspondent relationships, shrinking access to trade finance, and the forced migration of economic activity into cash and informality. The paradox is stark: a system designed to reduce risk ends up amplifying it by excluding those least able to absorb the shock.

Climate governance reproduces the same pattern. Moral consensus is abundant; fiscal delivery is not. Emerging markets are asked to internalize climate commitments while operating under severe budget constraints and limited access to concessional finance. When climate shocks occur, they do so in economies already weakened by debt distress and financial exclusion. The gap between promises and protection widens, and adaptation becomes another unfunded mandate imposed by a system that confuses declarations with capacity.

Even geopolitical coordination, often framed through security alliances, feeds this asymmetry. Strategic decisions taken among major powers reverberate through energy prices, trade routes, sanctions regimes, and capital flows. Emerging markets experience these shifts not as strategy, but as volatility imposed from the outside, with no seat at the table where the trade-offs are decided.

What unites these experiences is not failure of intent, but failure of design. Global governance today excels at producing narratives of responsibility while lacking instruments of execution. It convenes often, but intervenes late. It recognizes risk, but redistributes its cost downward. In doing so, it transforms coordination forums into amplifiers of fragility for those already on the edge.

Lebanon is not an exception in this story; it is a warning. It demonstrates what happens when a system optimized for dialogue encounters a crisis that requires speed, hierarchy, and accountability. The lesson is uncomfortable but unavoidable: global governance has become highly effective at managing appearances, and dangerously ineffective at managing consequences.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Annahar

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook