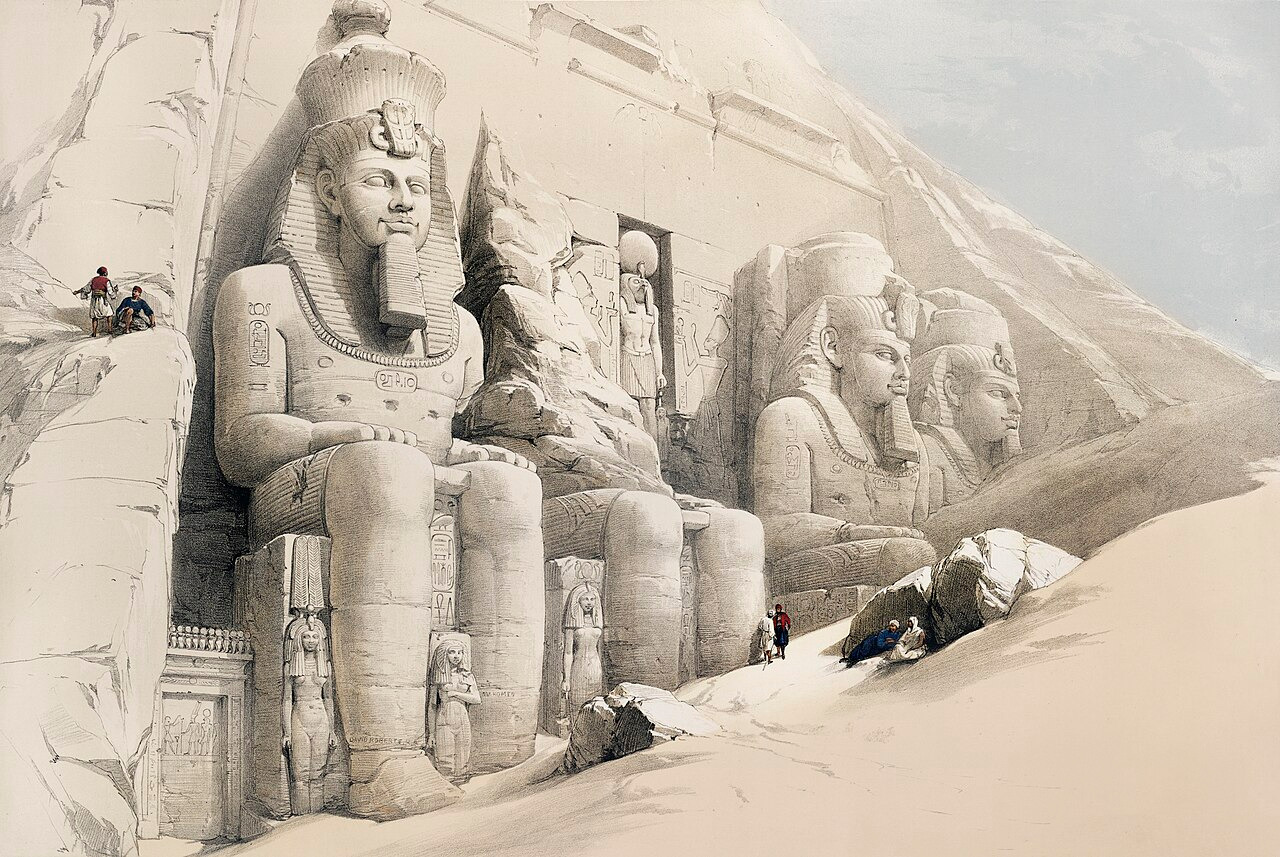

Ramses II and Nefertari immortalized in Abu Simbel Temples

King Ramses II’s love for his wife, Queen Nefertari, was as eternal as the stone that bears their legacy. The temples themselves tell the story, particularly the twin temples of Abu Simbel, built in the 13th century BC south of Aswan. One temple was dedicated to the king, the other to his queen, reflecting her extraordinary status - so much so that she was celebrated as “the one for whom the sun rises.”

However, the Abu Simbel Temples were more than a testament to rare royal love - they were a carefully crafted religious and political statement, through which Ramses II sought to immortalize his name and showcase Egypt’s power and prestige along its southern borders.

The Abu Simbel Temple complex is regarded as one of ancient Egypt’s greatest architectural masterpieces, carved entirely into the heart of a mountain in a strategic location overlooking Nubia. The larger temple was dedicated to the gods Ra-Horakhty, Amun, and Ptah, while also deifying Ramses II himself. The smaller temple honored the goddess Hathor and Queen Nefertari, with the rare distinction of featuring statues of the queen and king of equal size on its façade - a testament to Nefertari’s significant religious and political stature.

One of the most remarkable features of the Temple of Abu Simbel is its solar alignment, which occurs twice a year - on February 22 and October 22 - when sunlight penetrates the temple’s 60-meter-long front corridor to illuminate three statues inside the sanctuary: Ra-Horakhty, Ramses II, and Amun. The statue of Ptah, the god of the underworld, remains in shadow.

Professor Mahmoud Hamed El Hosary, a lecturer of antiquities and ancient Egyptian language at New Valley University, emphasizes that this phenomenon was no accident; it was designed with extraordinary scientific precision, showcasing the ancient Egyptians’ advanced knowledge of astronomy and architectural engineering.

El Hosary notes that there are several interpretations of the solar alignment’s significance. Some link it to the start of the agricultural season and the cycle of flooding and cultivation, while others associate it with royal ceremonies. What is scientifically certain, however, is its connection to solar faith and the broader religious and political symbolism of the state during Ramses II’s reign.

In the 1960s, the Abu Simbel Temple faced the threat of submersion due to the construction of the High Dam and the creation of Lake Nasser, prompting an unprecedented international effort. In 1960, under UNESCO’s supervision, a global campaign was launched to save the Nubian monuments. The temples were carefully dismantled into thousands of stone blocks, each meticulously numbered, and then reconstructed on an artificial hill 65 meters higher and roughly 200 meters back from their original location. Remarkably, their astronomical alignment was preserved, ensuring that the solar phenomenon continued with only a one-day shift from its original dates.

The temples were first brought to wider attention in the early 19th century when Swiss orientalist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt noted the site, followed by Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni, who successfully entered the temple in 1817. Later, British writer and traveler Amelia Edwards helped document the solar alignment phenomenon, connecting it to solar faith and the concept of divine kingship.

El Hosary concludes that Abu Simbel is far more than an archaeological site - it is an engineering and astronomical marvel, as well as a lasting symbol of royal love. Today, it stands as a testament to the genius of the ancient Egyptians and continues to inspire the world as both a cultural treasure and a major tourist destination.

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook