New illiteracy marginalizes arab readers and endangers cultural identity

Statistics concerning literacy trends in the Arab world reveal persistently high illiteracy rates, while reading levels remain alarmingly low, with the average Arab reading only one book per year or even less. This reality signals the rise of a new form of illiteracy that erodes collective consciousness and cultural identity, distancing individuals from their history and weakening their sense of belonging to and engaging with public life. It also prompts broader concerns about the ability of societies with limited knowledge to participate effectively in building a state and addressing its challenges.

In this report, Annahar spoke with Habib Sayah, an Algerian novelist and academic, Muhamad Jabaiti, a Palestinian novelist, Rim Najmi, a Moroccan journalist and novelist, and Algerian poet Najwa Obeidat, to discuss the impact of the new illiteracy on the future of culture in the Third World.

Habib Sayah: “Reading is fundamentally rooted in a national project.”

“I participated in the People's University in the late 1970s, when literacy was part of a socialist-oriented community project aimed at lifting the injustice suffered by millions of Algerians who had been deprived of education and learning by colonial France,” Sayah said.

He explained that the social project could not succeed while workers, peasants, and artisans remained unfamiliar with even the basics of reading and writing. In Sayah’s view, literacy campaigns not only contributed to the project’s collapse but also created a sense of shame among people, who feared others might discover that they were illiterate—even when those “others” often needed learning just as much. Over time, literacy became a bureaucratic enterprise run by designated “cadres” and “teachers,” which stalled the momentum that had once driven NGOs, factories, and “model” farming villages. “For me, the true models were the pioneering Iraqi literacy experience and those of several Latin American countries,” he said.

“Personally, I wonder how a ruling party could accept millions of illiterate people into its ranks without requiring members to read and write,” he said, noting that left-wing movements historically viewed literacy as essential for individual development and social progress. “Today, literacy has become a thing of the past. That was yesterday.”

Sayah suggested that part of the problem may lie in a deeper cultural pattern—a tendency toward withdrawal from reading that cultural sociology could examine. According to Syayah, “there is no cultural heritage that pushes us to resist ignorance in its educational sense.”

This absence of a reading culture, Sayah added, has shaped a new social reality: parents who do not read still appear entirely “normal” to their children, whether those children are in school, high school, or university. This happens even when the parents themselves are highly educated—professors, engineers, doctors, or senior officials.

In such an environment, Sayah argued, illiteracy inevitably takes root. “The act of reading, in the sense intended here, must be part of a national project built on planning, implementation, and continuous follow-up—just as it is in countries that view reading as the core of their existence, the way they come to know themselves, and through that, know others.”

Muhamad Jabaiti: “We suffer from even more severe illiteracy!”

As many countries celebrate the decline of traditional illiteracy, Jabaiti warns that the Arab world is confronting a far more serious challenge: the rise of superficial knowledge and widespread misinformation. “Small screens have become a source of fragmented, fleeting information,” while the role of books—once central to building awareness and critical thinking—continues to shrink.

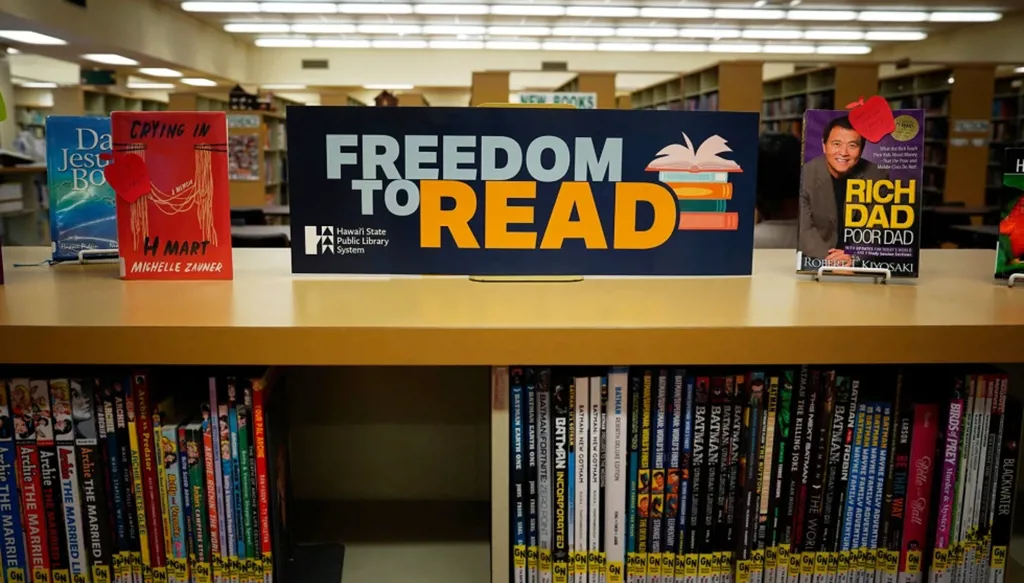

This shift toward social media consumption reshapes how people see themselves and the world, often leading to distortion, polarization, and blind imitation of trends. The absence of deep, critical reading has left the region vulnerable to extremism and shallow discourse. As Jabaiti emphasizes, literacy should mean more than the ability to spell words; it should reflect “the awareness and freedom” that come from meaningful engagement with books, ideas, and public libraries. Restoring that culture of reading, Jabaiti argues, is essential to protecting societies from intellectual and psychological decline.

Rim Najmi: “The publisher is not a philanthropist.”

Although the Arab world’s reading rates remain low compared to Europe or Asia, Najmi cautions against the claim that “Arabs do not read.” As explained by Najmi, “if there were no readers, there would be no publishing in the Arab world… a publisher is not a philanthropist he is also a businessman. Without sales, the publishing market would not survive, nor would the number of publishing houses—which continues to grow each year.” Despite ongoing challenges—including book prices and inconsistent reading habits—publishers continue to report solid sales at events like the Rabat Book Fair, and reading groups across Morocco, Egypt, and Jordan are helping cultivate active communities of discussion and engagement. While there are challenges related to reading habits and the price of books—which can be expensive for certain groups—but this does not negate the existence of an active market for publishing and writing in the Arab world, Najmi pointed out.

Najwa Obeidat: “Technology has overtaken the minds of entire generations.”

According to Obeidat, “it is unfortunate that people have moved from traditional illiteracy, which was defined by a lack of reading and writing skills and was often an inevitable fate due to colonialism and poverty, to a more dangerous form of illiteracy, which is a chosen illiteracy in the age of science, knowledge, and technology.” Instead of reading deeply, many now rely on rapid, fragmented bursts of information that weaken attention, critical thinking, and the ability to interpret events objectively.

This “mental decay,” as Obeidat describes it, is evident in how even highly educated individuals struggle to read a long, analytical article or engage in meaningful research. Technology, despite making information widely available, has “enveloped the minds of entire generations,” limiting their ability to absorb, analyze, and think independently. The result is a decline in public awareness and susceptibility to misinformation—what Obeidat calls a form of intellectual deterioration that threatens society’s capacity to advance.

“If you want to destroy a people, destroy their library,” Obeidat noted’ “They did not only destroy our libraries—they destroyed our minds, leaving us afflicted with what can only be described as a disease of mental decay.”

Messenger

Messenger

Whatsapp

Whatsapp

Threads

Threads

Email

Email

Print

Print

X

X

Facebook

Facebook