By Carmen Geha

“It is painful and draining,” my friend tells me, “As much as it is rewarding and important, it is also exhausting.” My friend is a long-time political activist who, like many of us, has tried in different ways to build movements, organize protests and express solidarity while living under the Lebanese violence and corruption. The warlords, who took charge of building a state in 1989, failed miserably and led us to be governed by a mafia and militia rule. To survive, the mafia and militia have mastered a system of violence and exclusion. The system excludes us from our rights, from representation, from access to decision-making, from mobility; depending on where we are born or which sect we are born into, how much money we make and where we vote; we are excluded altogether but often in different ways. For example, women’s rights differ across 15 religious courts with no single unified civil status law.

This system hurts us personally, individually and collectively. We each have distinct personal experiences and scars, from kidnapping, to losing loved ones, to being shot at, to losing all our savings. These personal pains affect the way we see the country and our role in it; pain affects our priorities, and the personal shapes our demands and theories of change. We know that the personal is political from decades of research and activism inspired by the feminist movements across the world, but how often do we apply this lens and how do we navigate the personal and the political?

For my friend, and many like her, these different pains make it challenging to build one collective unified movement. But in my opinion, this is also our source of strength. Why? Lebanon is not a dictatorship that can be ousted all at once – we tried – but Lebanon’s system is made up of a network of corrupt warlords with their hands on the judiciary, private sector, foreign relations, schooling, health and even sports.

“It is painful and draining,” my friend tells me, “As much as it is rewarding and important, it is also exhausting.” My friend is a long-time political activist who, like many of us, has tried in different ways to build movements, organize protests and express solidarity while living under the Lebanese violence and corruption. The warlords, who took charge of building a state in 1989, failed miserably and led us to be governed by a mafia and militia rule. To survive, the mafia and militia have mastered a system of violence and exclusion. The system excludes us from our rights, from representation, from access to decision-making, from mobility; depending on where we are born or which sect we are born into, how much money we make and where we vote; we are excluded altogether but often in different ways. For example, women’s rights differ across 15 religious courts with no single unified civil status law.

This system hurts us personally, individually and collectively. We each have distinct personal experiences and scars, from kidnapping, to losing loved ones, to being shot at, to losing all our savings. These personal pains affect the way we see the country and our role in it; pain affects our priorities, and the personal shapes our demands and theories of change. We know that the personal is political from decades of research and activism inspired by the feminist movements across the world, but how often do we apply this lens and how do we navigate the personal and the political?

For my friend, and many like her, these different pains make it challenging to build one collective unified movement. But in my opinion, this is also our source of strength. Why? Lebanon is not a dictatorship that can be ousted all at once – we tried – but Lebanon’s system is made up of a network of corrupt warlords with their hands on the judiciary, private sector, foreign relations, schooling, health and even sports.

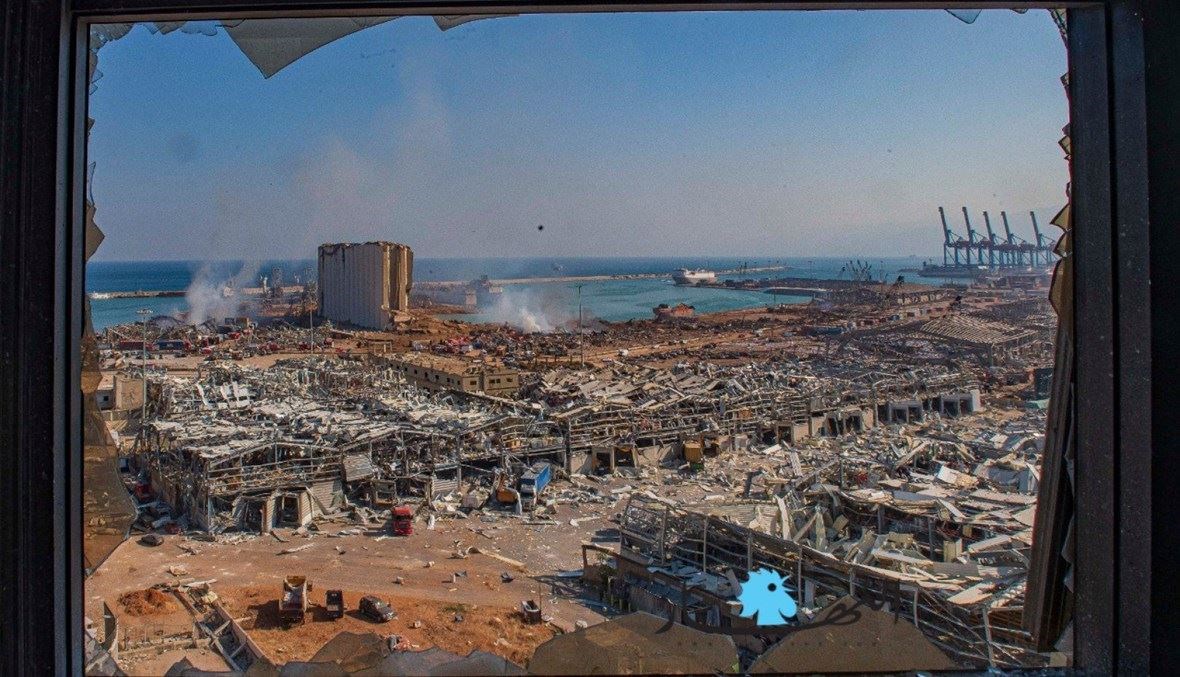

The only way to gain grounds against such evil is by attrition, and so a multi-faceted strategy with multi-stakeholder mobilization is a good thing, as long as we can understand and support each other. What is this attrition? It is winning one battle at a time by creating a horizontally based support for issues and strategies that can weaken the grip of politicians over our lives. From the union of depositors, to student elections, to the battle against corruption and foreign aid, if we join forces without necessarily uniting, we will gain ground. One historic incident of this sort was the national and international outcry against aid going to corrupt and culprit public institutions – a battle we won after the explosion. Now we must think of long-term institution building, and in order to do that, we must face our own scars and the scars and fears of others around us, because all our politics are personal. Here are two lessons we can learn from our own experience in movement building, over the last 16 years or so.

Narratives and Words Matter, but Actions Matter More

Narratives create stories and help us make meaning of specific situations and events. For movements, narratives explain how and why people are coming together and what they want to achieve. Statements, petitions, slogans, protest chants and press conferences are all ways in which we showcase our narrative. Our narrative since the 2015 garbage crisis has been that this political class is responsible for our tragedies, from failing to recycle trash all the way to leaving explosives at the port using our bodies as human shields.

Narratives and Words Matter, but Actions Matter More

Narratives create stories and help us make meaning of specific situations and events. For movements, narratives explain how and why people are coming together and what they want to achieve. Statements, petitions, slogans, protest chants and press conferences are all ways in which we showcase our narrative. Our narrative since the 2015 garbage crisis has been that this political class is responsible for our tragedies, from failing to recycle trash all the way to leaving explosives at the port using our bodies as human shields.

Right now, the overarching narrative is that the humanitarian disaster is caused by the political system and the failure of politicians to undertake reforms. But while narratives are important, they have also been the reason for so many groups arguing, so many friendships ruined, so many networks disrupted – words matter but actions matter more. At this historic juncture, while the world is listening and watching, we need to do more than just talk, this time we need to construct institutions and movements that can resist the prevalent narrative but also the exclusionary policies and practices that shape the political system. We need to experience inclusion, equality, protection and solidarity – not just demand it so that we can together not just beat the criminals by words, but by action.

We Need Each Other, Personally and Politically

We are all drained, not just my friend. Life in Lebanon has turned into a daily battle for the bare minimum. We need each other and this need is dual; it is personal and political in deeply intertwined ways that we cannot separate. If we are to build a political vision, we need to understand each other’s personal histories, pains and aspirations. We may not share the same priorities or fears but we can validate and resonate each other’s demands, while recognizing different strategies to achieve those demands. Some see elections as the key strategy for confrontation, others want to build cooperatives, some want to focus on services free of clientelism, and others want to live abroad and advocate from foreign capitals, and this is more than okay, this stratification is important for the attrition of the regime.

We Need Each Other, Personally and Politically

We are all drained, not just my friend. Life in Lebanon has turned into a daily battle for the bare minimum. We need each other and this need is dual; it is personal and political in deeply intertwined ways that we cannot separate. If we are to build a political vision, we need to understand each other’s personal histories, pains and aspirations. We may not share the same priorities or fears but we can validate and resonate each other’s demands, while recognizing different strategies to achieve those demands. Some see elections as the key strategy for confrontation, others want to build cooperatives, some want to focus on services free of clientelism, and others want to live abroad and advocate from foreign capitals, and this is more than okay, this stratification is important for the attrition of the regime.

We are increasingly seeing a multi-faceted solidarity; you don’t need to have been sexually harassed or raped to validate this need and join the women’s call for protective measures, you don’t need to be a journalist to protest for free speech, you don’t need to be a person of colour to ask to abolish kafala, and you don’t need to have lost a loved one on August 4th to demand justice. Validating each other’s priorities and supporting multi-stakeholder mobilization and strategies is better than arguing about who is right because we are all hurt. We need each other not on the streets but in the intimate networks of friendship and the interpersonal support system that shapes our entry point into the political. We need to be able to turn to each other not just to share statements on whatsapp but to express doubt, fear, fatigue, and share moments of grief and joy.

Moving On

These are two lessons that come to mind as we approach the one year of the Beirut port explosion, with no headway in the investigation, no reform, no accountability and no justice. We are forced to reckon with our own fatigue, worry, fear and exhaustion. One way to muddle through is to talk together about what we have learnt from past experiences, what we need to do better and most importantly what we can do if we come to terms with our personal scars and shape our political journeys. While we undertake actions across a spectrum of issues, let us also find time and energy to confront our scars and chart a trajectory of attrition, because the criminal tyrants in charge are not a dictator that will fall all at once, but a system and a network that we need to topple one milestone at a time.

Moving On

These are two lessons that come to mind as we approach the one year of the Beirut port explosion, with no headway in the investigation, no reform, no accountability and no justice. We are forced to reckon with our own fatigue, worry, fear and exhaustion. One way to muddle through is to talk together about what we have learnt from past experiences, what we need to do better and most importantly what we can do if we come to terms with our personal scars and shape our political journeys. While we undertake actions across a spectrum of issues, let us also find time and energy to confront our scars and chart a trajectory of attrition, because the criminal tyrants in charge are not a dictator that will fall all at once, but a system and a network that we need to topple one milestone at a time.

*Carmen Geha is an Activist and tenured Associate Professor of Public Administration and Leadership at AUB

اشترِك في نشرتنا الإخبارية

اشترِك في نشرتنا الإخبارية